After spending a few days relaxing in Cochabamba, we decided to head to Potosi. We agreed to skip Sucre, the capital of Bolivia, as it was more of a city with a national park nearby that had dinosaur footprint. That didn’t wow us much. Instead, Potosi is known for the mines and is on the way to Uyuni, our main destination in Bolivia.

Getting There

Getting to Potosi from Cochabamba was a challenge. There were no day buses when we arrived at the terminal at 8am. Therfore, we took a bus to Oruro from Potosi which took around 4 hours to reach there. Oruro’s terminal was like a village terminal in India with people carrying huge cartons of luggage everywhere.

We bought a bus ticket for the next bus at 3pm for a 4 hour bus journey. Before this, we had heard about Bolivians protesting all big and small things by blocking roads. However, this time there was talk in the terminal that the main road was blocked. The bus would go from a longer route through the desert.

The bus journey took 8 hours but the bus went through some incredible landscapes. We saw lakes, mountains, small salt flats, sand dunes, llamas, vicuñas and quinoa fields. We reached the hostel at 10:30pm and were a bit groggy the next morning.

Hot Showers At Last

Hostel Casa Blanca Potosi was one of the more expensive hostels in Potosi to stay at. However, our hostel in Cochabamba had a suicide shower (you have the choice of showering cold or getting electricuted while showering warm) and we chose cold showers for a few days.

While the hostel was great with a kitchen, breakfast, bar and a great chilling area, we loved the hot showers the most. It was probably the first time we have been picky over something like this. We didn’t regret it and had the longest showers during our time in South America!

Mine Tour

A long time ago I saw a documentary or a news piece about mines of Potosi. Each day, tourists go into the mines to see and understand about the lives and work of miners who have been mining the Cerro Rico mountain for over 500 years. It sounds touristy and adventurous but it’s a must do in South America to understand the hardship miners have gone through.

To benefit the miners, we decided to use a tour company whose guides were ex miners themselves. We signed up with Big Deal Tours on the morning of the tour and met other tourists. Though the tour was 50 Bolivianos per person, just over USD 7, more than other tour companies, it allowed us access to the minerals refinery as well as having the tour legitimate and safe.

Our first stop was the miners market where we bought gifts for miners. As we are entering their domain, its best to respect their work and help them out with some juice and coca leaves.

The next step was to get the equipment for safety including waterproof overalls, rubber boots and helmets with lights as well as a waterproof bag for our gifts. We weren’t meant to carry anything on us though I carried my phone and wallet in my pants, under the plastic pants. We set off from the equipment house to the mineral refinery. The refinery looked over Cerro Rico, the main minerals site of Potosi.

Our guide, Wilson gave us the lowdown on the mountain and the mining in Potosi. Cerro Rico has been mined for over 500 years starting with the Spanish. Once they discovered silver in the mountain, they brought African slaves to work in the mines. However, the Africans couldn’t survive at 4000 meters and eventually the Spaniards enslaved native Quechuas who lived in the region. Their story is quite sad as they were fed poorly and given coca leaves which are a hunger and thirst suppressant. This continued until the Spanish rule and also until the silver ran out. Millions died mining for the Spanish and Bolivia never received any benefits. Bolivia tried a nationalized company for mining but it didn’t work out. Today there are many cooperatives for whom the miners work.

The refinery crushed the rocks full of minerals and made it into a paste of minerals for export to China. The amazing thing was that Bolivia is mineral rich but industrially poor. It sends its minerals to China and other countries and then buys back the goods for use. After spending some time at the refinery, we headed towards the mines. Along the way, we took some selfies and photos with the beautiful mountain with a sad story.

As we headed into the mines, the smell of dynamite and chemicals was everywhere. Wilson warned that when we heard him yelling about wagon, we had to stick to the wall of the mine in case a flying wagon killed us. The entrance of the mine was full of water on the ground and smell of chemicals.

As we went in deeper, the mine became darker and the air thicker. We could only see with our headlights. Occasionaly, a wagon being pushed by miners would come and we would all stick to the wall.

During our journey deeper into the mountain, we would see miners heading back to change coca. This meant they had been working for 4 hours and it was time to rest. Wilson would talk to these miners and ask questions and then translate aspects of their lives for us and we would give them the gifts we brought along.

At one point, he sat us down on rocks and explained the cooperatives and the plight of the miners. Cooperatives had several layers of miners. New miners had to work for 3 years to be made full-fledged and could then work the mineral veins which ran through the mountain. These mineral veins could be thick or thin, could be full of minerals or simply rubbish. It all depended on luck and how well you got along with other miners. A new miner who had a fight could be kicked out and an experienced miner who had a fight could be elected out. Wilson had been a miner for 24 years, he had gone up the ranks but his mineral vein had ran out twice making him poor and vulnerable. He told us only a funny miner could survive for long as he would hide his pain and not fight. This explained his funny attitude.

After this we walked from one mine to the other using 3 ladders. We basically escalated levels in the mountains. In a confided space where we could hardly stand up straight, climbing a vertical ladder was a bit of relief. Except we couldn’t watch where we were going, unless we wanted dust and sand in our eyes.

We mainly did this to see El Tio Benito and also to cross the mountain and meet our bus. The miners have a mix of Catholic and indegenous beliefs. El Tio is the God of the mountain and his idol, though a bit odd, is in several places in the mountain. The miners believe that he keeps them alive and gives them luck (fertilises) for minerals. They give him offerings of cigarettes, alcohol and coca leaves. More importantly, they drink a litre of pure 96% alcohol on Fridays to please him.

We mainly did this to see El Tio Benito and also to cross the mountain and meet our bus. The miners have a mix of Catholic and indegenous beliefs. El Tio is the God of the mountain and his idol, though a bit odd, is in several places in the mountain. The miners believe that he keeps them alive and gives them luck (fertilises) for minerals. They give him offerings of cigarettes, alcohol and coca leaves. More importantly, they drink a litre of pure 96% alcohol on Fridays to please him.

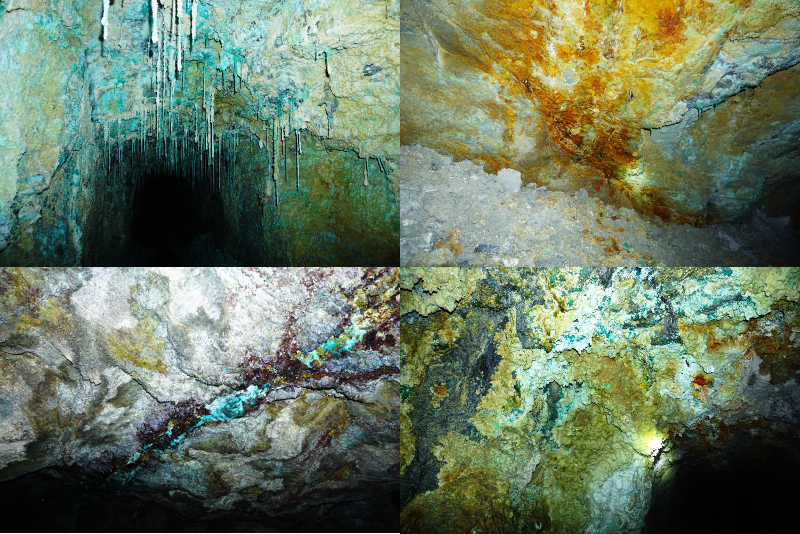

On a sad note, we all had a sip of pure alcohol (which tasted horrible) and started to exit the mountain. Along the way, we went through an abandoned mine which is now full of beautiful stalagtites and stalagmites.

The final stretch was the toughest, it was all very short so we had to walk squatting. 10 minutes of this and our legs were smashed. Finally, we were out of the mountain with a greater respect for miners than we had before. A must do in Potosi!

Convento San Fransisco

Another highlight of Potosi was the 16th Century Convent of San Fransico. We took a tour of it for 15 Bolivianos per person, just over USD 2. Our first stop were the catacombs which we saw after the Cathedral of Cuenca. However, these were much older with skulls and bones still on display. It was a little scary and we were happy to get out of there.

Our next stop was the main reason for which we had come to the convent. The tour takes you to the roof of the convent. The domes and spires are tiled and the story goes that the natives who didn’t want to die in the mines came to the convent and worked and lived here. While the domes were beautiful, the best thing was the view of the city and the mountain. The tour is worth for this alone!

Our next stop was the main reason for which we had come to the convent. The tour takes you to the roof of the convent. The domes and spires are tiled and the story goes that the natives who didn’t want to die in the mines came to the convent and worked and lived here. While the domes were beautiful, the best thing was the view of the city and the mountain. The tour is worth for this alone!

We then saw the church with its 12 brick domes representing Jesus and the Apostles. It was one of the first times in Latin America that we saw a Brown Jesus with black hair. This along with some paintings by native artists made us love this convent. The native artists painted all the negative characters in the bible as Spanish. A perfect example of protest in art.

Casa De La Moneda

Casa De La Moneda were the mints set up by the Spanish around Latin America to press coins. Potosi was the most famous of them all as the quality of silver was meant to be the best in the world. We arrived for an English tour to find out that there was none at that time. As we were leaving that day, we refused to come back later. After a long wait, a lady came to give us the tour.

From the start she wasn’t happy to give us a tour as it was only for 2 people. Moreover, The fact that I can speak some Spanish ticked her off even more. Anyway, she showed us the original coins minted here and told us about their value. The most interesting thing was that the letter PTSI were used on top of one another for Potosi coins. Their reputation was so high that to this day, SI on top of one another is used as the dollar symbol.

We saw many more rooms which had printing presses, foundaries, silver presses, silver wares, minerals from the mountain and modern Bolivian coins. The best example of outsourcing? Bolivian coins are made in Chile and Canada as its too expensive to mint them in Bolivia. An informative museum at 40 Bolivianos per person, under USD 7, but certainly an expensive one.

Bus to Uyuni

We took a 1:00pm bus to Uyuni which was meant to be the 12:30pm bus but this is Bolivia and no one complained. As the bus left Potosi, the view became breathtaking. There were mountains and valleys with llamas grazing in the distance. Shruti even managed to photograph a llama crossing sign.

It was only a 4 hour ride but it seemed much longer in good way as we went over canyons, hills and mountain passes. As the bus climbed the final hill before Uyuni, the vast high desert with a city in the middle appeared out of nowhere. It was a lovely sight. If we looked in the distance, we could see world’s biggest salt flats. We were near Salar de Uyuni.

One thought on “Potosi – Effects of Colonialism”

Comments are closed.